Historic local election victories across the country for people of color. Local elections had historic results, leading to Black, Asian politicians taking a seat in office. Staff video, USA TODAY

WASHINGTON — Mercedes Krause faces an uphill climb to unseat incumbent Nevada GOP Rep. Mark Amodei.

Nevada’s 2nd Congressional District, which is about 67% white, 2% Black, 23% Hispanic, 4% Asian American and 2% Native American, has never elected a Democrat or a person of color since it was created after the 1980 Census.

But Krause, who is Native American and Hispanic, said her primary win in June over six Democratic men shows voters want change.

“Part of me is just defiant. Can we start doing something different as a whole?” Krause said. “I feel like people do want a woman’s voice. I feel like people do want to have wider representation.”

Political experts say in recent years more candidates of color— Democrats and Republicans — are running in predominantly white districts and winning. Those efforts, they said, particularly increased in the wake of George Floyd’s death in 2020 and the push for more diversity from corporate boardrooms to Congress.

Democratic candidate for Nevada’s 2nd Congressional District Mercedes Krause talks with supporters while attending the Douglas Democrats Election Kick Off and Fundraising BBQ at Mormon Station Park in Genoa on July 30, 2022. Jason Bean/Reno Gazette Journal

Some lawmakers and experts predict the trend could continue this midterm as both sides look to a more diverse pool of candidates to boost their chances to win seats—and not just in predominantly minority districts.

‘‘We shouldn’t assume that people of color… can only win in the minority-majority districts,’’ said Rep. Raul Ruiz, chairman of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus and a Democrat from California. “We’re seeing an increasing trend of impeccable candidates who do great work for the local communities, who are from their communities, who are winning their elections.”

Candidates of color face extra hurdles running in predominantly white districts, experts said. They have long complained about working harder than their white counterparts to raise funds, tap political networks and get support from national parties while also having to overcome discrimination and racism. All of these factors may help explain why people of color remain underrepresented in Congress.

“I’ve gotten the most support through the two organizations that are working for the Native vote,” Krause said. “I’ve gotten some support at the state level too, but … I do need that larger Democratic support.”

Rep. Lauren Underwood, a Democrat from Illinois, is one of a growing number of candidates of color winning in mostly white congressional districts. Carolyn Kaster, AP

2018 was a pivotal year for candidates of color

Experts point to 2018 when more candidates of color ran—and won— in predominantly white districts as setting the stage for other efforts to follow.

It “was a breakthrough year for Democrats and for Black Democrats in majority white districts,’’ said David Wasserman, a senior editor for the nonpartisan Cook Political Report.

He said Democrats embraced a diverse group of candidates that year, including Lauren Underwood from Illinois, Jahana Hayes from Connecticut and Lucy McBathfrom Georgia.

Rep. Jahana Hayes, D-Conn., left, and Rep. Lauren Underwood, D-Ill., talk during a markup in the House Education and Labor Committee on Capitol Hill in Washington, March 6, 2019. J. Scott Applewhite, AP

Of the 13 women of color newcomers elected to Congress in 2018, five were from majority white districts, according to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University in New Jersey. And of the 30 incumbent women of color elected, four were from majority white districts.

In 2020, three of the eight women of color elected came from majority white districts. Two were Republicans, Nicole Malliotakis of New York and Michelle Steel of California. The Democrat was Marilyn Strickland from Washington.

Part of the change may have been because of an increasing pool of women candidates of color, said Kelly Dittmar, director of research at the Center for American Women in Politics.

‘’You can’t limit them then to only majority-minority districts as has been done historically,” said Dittmar.

Some candidates challenged the notion that they couldn’t win in mostly white districts.

“It’s a bit of women pushing back and saying, ‘I’m not going to be deterred by those who are thinking that I cannot win in this space,’’’ Dittmar said. “And then they win.’’

Wasserman attributes the trend in part to more white college-educated Democratic voters demanding Congress be more diverse.

“That’s accelerated in the post George-Floyd era,’’ he said, noting that in 2020 there was a surge in support for Black candidates, including Jamaal Bowman, a Democrat from New York.

Michelle Steel, a Republican from California, won her seat in 2020. Paul Bersebach, AP

More Republicans are supporting a diverse slate of candidates, Wasserman said. He noted that in 2020, the 16 Republicans who flipped Democratic-held seats were women or minorities.

And more Republican voters are embracing candidates who defy the stereotypes of who conservatives are, Wasserman said.

“Republican primary voters want to send a message that they’re not racist like the so-called liberal media is painting them out to be, so we’re seeing Black and Hispanic candidates perform very well in Republican primaries,’’ he said, noting, for example, Jennifer-Ruth Green from Indiana’s 1st District. “There are an awful lot of Republican candidates of color who are breaking through and that’s quite a contrast with just four years ago when 29 of the Republican’s 30 freshmen were white men.’’

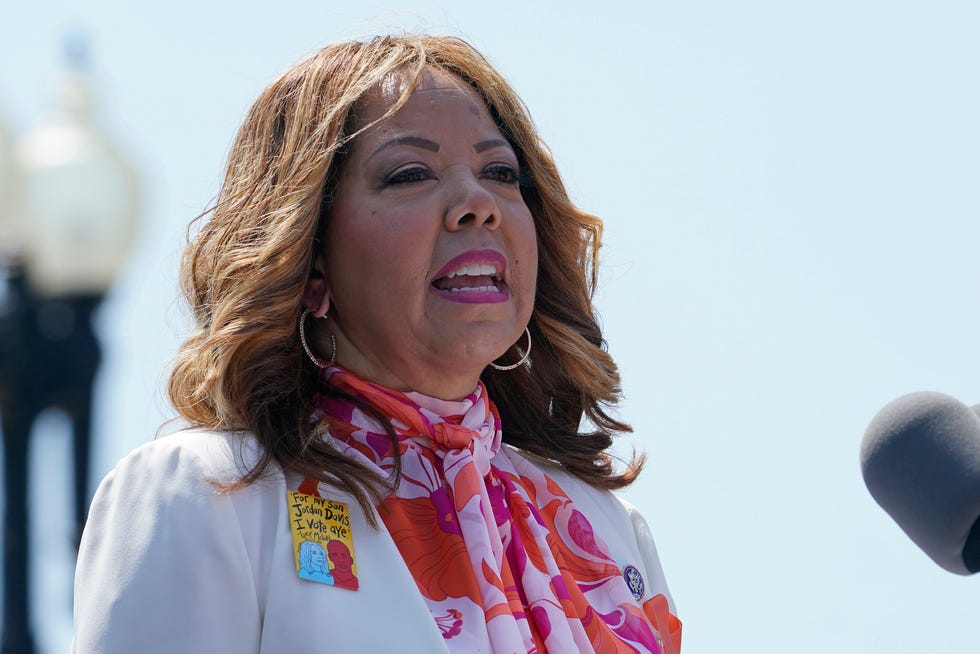

Rep. Lucy McBath, D-Ga., is one of several lawmakers of color who won their races in 2018 in diverse congressional districts. Susan Walsh/AP

Gender matters in elections

Women of color may have an advantage running in predominantly white districts, some experts said.

“Minoritized women are not seen the same way that scholarship says that very ethnic men are seen,” said Nadia Brown, a political scientist at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

Brown said because of gender stereotypes, women are seen as “softer” and “kinder.” When they advocate for racial issues, it doesn’t hurt their campaign as much, Brown said.

“It will be done so in a way that is more societally permissible because their gender softens whatever kind of harsh racialized rhetoric that people might think that they have,” Brown said.

One example experts point to is McBath’s push to reduce gun violence. Her son was fatally shot in 2012.

“White women in those districts respond to this,” Brown said. “They empathize as a mom in ways that would not probably happen if it were a Black male candidate running.’’

McBath initially faced skepticism when she ran for Georgia’s 6th Congressional District, which is 57.5% white, 14% Hispanic, 12.7% Black and 12.9% Asian. She defeated incumbent GOP Rep. Karen Handel in 2018.

“I remember it was four or five years ago, this topic came up of if people of color, especially women of color, can represent districts that are majority white,” said A’shanti F. Gholar, president of Emerge, an organization that trains Democratic women to run for office, including McBath and Krause. “The notion that they can’t is completely antiquated and outdated because when you looked around you saw so many people of color, women of color, who were running and winning. And now it continues to hold true.”

Winning could be harder this election cycle

Bowman, a freshman congressman, said authenticity was a key to his win two years ago in his racially diverse district in New York.

He’s banking on that happening again—even as new maps have made the 16th Congressional District whiter.

Bowman, a former educator, defeated long-time Democratic incumbent Eliot Engel, who is white, in 2020 and is fending off challengers. The primary is Aug. 23. His newly drawn district is 40% white, 29% Hispanic, 20% Black and 7% Asian American, according to the Center for Urban Research at the City University of New York.

Bowman said his campaign and those of other candidates of color in diverse districts reflect a change.

“I think that shows an evolution and a shift in the consciousness of the American people being manifested in electoral politics,’’ said Bowman, who said his progressive ideology crosses demographic lines. “They want quality leadership, and if the African American or Black person is representing someone that they believe will be a quality leader, they’re going to support that person.’’

Rep. Jamaal Bowman, D-N.Y., said the progressive ideology, which he calls a unifying principle, crosses all backgrounds in his diverse district. Eduardo Munoz Alvarez/AP

In the past, many lawmakers of color in Congress have come from majority-minority districts.

Former Democratic Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick said when he headed the Department of Justice’s civil rights division, he defended the creation of the first majority-minority districts, which included the South Carolina district that House Majority Whip James Clyburn represents. Clyburn is now the highest ranking African American in Congress.

Deval said voters of color want lawmakers who will represent their interests irrespective of race.

“We didn’t presume, and I don’t think anybody should, that the only candidates a Black voter will vote for are Black, or that the only candidates a brown voter would vote for are brown,” he said.

Deval, who co-chairs the American Bridge 21st Century, a super PAC, said voters are often energized by candidates who share their experiences.

Deval and other Democrats have raised concerns about the redrawing of congressional maps after the 2020 Census.

Rep. G.K. Butterfield, chair of the House elections subcommittee, said redistricting could reduce the percentage of Black voters and voters of color in congressional districts. Traditionally, many African American voters tend to support Democratic candidates.

“We all have a high level of anxiety because we know that state legislatures, especially those that are dominated by Republicans…they’re going to use every opportunity to maximize their political influence,’’ said Butterfield, a Democrat from North Carolina.

But Butterfield and other lawmakers contend candidates of color can also win in predominantly white districts and expect that will happen in November. And not all will be Democrats.

“I suspect you’d get some other Black Republicans nominated,’’ said Clyburn. “So diversity, yeah, it’s going to increase. A bunch of brown Republicans will be coming here. Diversity is one thing, partisan politics is another.”

Clyburn said he expects there will be more majority-minority districts in places such as Texas, a conservative-leaning state that saw rapid population growth in the 2020 Census, but that may mean more Black Republicans—not Black Democrats— will be elected to Congress.

Clyburn said about a third of the Congressional Black Caucus doesn’t come from predominantly Black districts. He said his own district will be less than 50% Black under a new congressional map.

“I told them you can draw anything you want to, I’m running,’’ he said.

House Majority Whip Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., said he expects more people of color from both sides of the aisle will be elected to Congress in November. Clyburn has been stumping for Democratic candidates across the country. Deborah Barfield Berry

Polls can be unhelpful

Experts said there’s no one strategy for candidates of color to win in mostly white districts.

Joseph Jones, a political scientist at Clark Atlanta University in Georgia, said a lot depends on the candidate’s district and issues in those communities. “You can’t put a template’’ on it, he said.

One challenge is relying on polls that show white people saying they support a candidate of color, but they don’t vote for them, Jones said.

He doubts many Democratic candidates of color will garner much support in some primarily white districts in part because of what he calls white “citizen insecurity,’’ which he describes as an imagined fear that something is about to be taken away.

“If the Democrats are thinking that we’re in a moment where minority candidates can run … in white spaces, whether it’s a Democrat or Republican, I would pause and have a serious, serious look at that,’’ he said.

But it helps when candidates of color, especially women, defy presumptions and win in mostly white districts, said Dittmar of the Center for American Women in Politics.

“Every time that happens it does at least push back against that and perhaps changes minds and thoughts about what is possible,’’ she said.